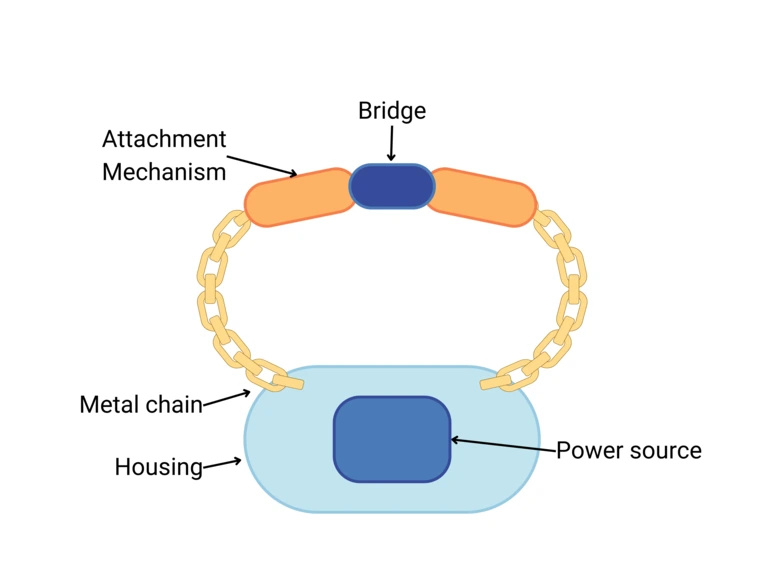

A virtual fence (VF) system typically consists of three main components: (1) a software interface that allows users to draw VF lines and define boundary zones on a digital map, establishing designated grazing areas and exclusion zones; (2) a GPS-enabled collar fitted around an animal’s neck, equipped with technology to track movement and deliver auditory and electrical cues to guide or restrict livestock distribution; and (3) base stations and/or cellular towers that facilitate communication between the software and the collars (Antaya et al., 2024; Ehlert et al., 2024). As of December 2025, 4 VF systems are commercially available in the United States. These trademarked systems include: eShepherd by Gallagher, Halter, Nofence, and Vence by Merck Animal Health. VF components from different manufacturers are typically not compatible or interchangeable. Although there are similarities across systems, each company offers a distinct collar design (Figure 1, Table 1) (Audoin et al., 2025). This educational material provides details on the attachment mechanisms, collar assembly, required deployment tools, and recommendations for achieving proper collar fit for each vendor

Across all systems, ensuring a proper collar fit is essential. A well-fitted collar allows animals to behave normally without discomfort, minimizes risk of injury, and ensures the correct delivery of VF cues. In any case, each VF company has recommendations on collar fit that you should follow for animal welfare reasons, and for a best use of the technology. If you are putting collars on growing animals such as heifers and steers, you will need to check the collar fitting every 6 to 8 weeks.

This publication is part of the Foundations of Virtual Fencing series. Other titles in this series include:

- Basics of a Virtual Fencing System

- Training and Animal Welfare

- The Vital Role of High-Quality Data

- Exploring the Complexities and Challenges

- Strategies for Collar Management

- Collar Deployment Basics

- Collar Deployment by Company

- Economics of Virtual Fencing

- Watch virtual fencing videos on Rangeland Gateway

Figure 1. Stylized generic VF collar showcasing attachment mechanism, a bridge, metal chains, collar housing, and power source (either non-rechargeable battery or solar rechargeable battery). The specific design will vary by vendor and model. Some designs use a belt rather than metal chains and a bridge. All collars include a breakaway mechanism for animal safety.

Amber Dalke, University of Arizona

| Features | eShepherd™ from Gallagher™ | Halter™ | Nofence™ | Vence™ from Merck Animal Health |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Housing Stores battery/technology | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Metal chains Helps deliver electrical cue | YES | NO | YES | YES |

| Belt-like design Helps deliver electrical cue | NO | YES | NO | NO |

| Bridge or strap Breakaway point | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Attachment mechanism Connects two ends of the collar strap | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Software updates Updates sent by the company remotely | YES | YES | YES | YES* |

| Individual animal tracking GPS location | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Collars with capability to identify animals in the field Light, sound | NO | YES | YES | NO |

| Customer support Response times may vary | App & Email | App & Email | ||

| VF system relies on base station* (needed for VF system to work) | YES | YES | NO | YES |

| VF system relies on cellular network* (needed for VF system to work) | YES | NO | YES | NO |

| VF software application | Application (computer & phone) | Application (phone & tablet) | Application (phone & tablet) | Web browser (computer & phone) |

| Contact information (VF is a rapidly developing technology. Contact the vendors directly for the most current information regarding price, hardware, and software capabilities.) |

eShepherd

Amber Dalke, University of Arizona

Gallagher is a New Zealand based company who bought eShepherd’s technology in 2016. The system became available in the US during spring 2024. The company specializes in collars for cattle. Their collars are not designed for small ruminants. Collars are solar powered and estimated to last between 7 and 10 years; however, they have not been deployed on US rangelands long enough to verify this. To use this system, collars must be purchased, and the hardware is covered by a 3-year warranty. A subscription must also be purchased. eShepherd is the only VF system that can communicate either directly to a cellular network or through base stations. A single Gallagher collar cannot do both. Base stations have a coverage of 2 to 4 miles depending on the environment.

Attachment mechanism

| Attachment | Attachment considerations | Tested | Effectiveness (5-Point Likert Scale) |

|---|---|---|---|

Version 1 silicone straps Image

Brian Allen, University of California Cooperative |

| Tested at the UCCE and SDSU (2024)* | Moderately effective |

Version 2 silicone straps Image

Brian Allen, University of California Cooperative Extension |

| Tested at the UCCE and SDSU (2025 to present)* | Effective |

Collar assembly

The Gallagher eShepherd collars arrive turned off and partially charged. Activate each collar by holding the included magnet (or any medium strength magnet) near the LED for about five seconds until the collar emits an escalating musical tone. An orange LED will blink while the collar attempts to connect to the network. Once connected, it blinks green and the collars will soon appear in the eShepherd Web App, downloadable at app.eshepherd. com. The green light will continue to blink periodically as long as the collar remains on with good battery charge and connectivity.

Before collaring livestock, place activated collars in direct sunlight for several hours to a day before attaching them to livestock to ensure full charge and connectivity. A flashing red LED upon activation indicates a low battery. The lithium battery is designed to have a long life and is not designed to be replaced by the user.

Repeat this process to turn the collar off. Hold the magnet near the LED. The collar will emit five short beeps, a descending tone, and show a solid purple LED to confirm deactivation.

Tools needed

No additional tools are needed to attach or remove collars (Table 2), but a 10 mm Allen wrench can make removing the locking clips much easier than by hand. For greater efficiency during collaring, prepare a numerical list of eShepherd collar IDs and pair each collar ID with the animal’s corresponding unique identifier, such as an ear tag number or Electronic IDentification (EID), as they are collared in the chute. Animal identifiers can then be entered into the eShepherd system either manually or via bulk upload. For bulk upload, log in, go to “Animals,” click “Create,” and select “Bulk Create – Download File” to get an excel file template for entering ear tag and EID data. Collars also contain radio-frequency identification (RFID) tags that can be paired with an animal’s EID using an EID reader wand.

Recommendations for proper collar fit

Attaching collars to livestock

Attaching collars can be done quickly. At the University of California Cooperative Extension (UCCE), fitting and collaring took about one minute per animal, excluding squeeze chute loading time. Collaring efficiency improves by setting up in advance to minimize time working on the animal. Line up collars by their ID numbers and organize locking clips in pairs (Figure 2). By collaring a few animals first, the user can estimate the average chain length needed for most of the herd, then pre-adjust the rest of the collars. The remaining chain will hang freely.

To attach the collar, position the animal in a squeeze chute with the neck exposed. Use a backing bar if necessary to prevent backward movement. Ensure the top arrow and cow emblems imprint on the collar face forward, aligning with the animal’s head (Figure 2). For animals prone to head movement, having two handlers is ideal. One handler passes the top strap over the animal's neck, and the other clicks it into place. With the animal’s head in a neutral position, check the fit by lifting the top strap until the collar contacts the underside of the neck. A proper fit should be snug while permitting approximately 4 inches of space between the strap and the top of the neck. Ensure equal chain link lengths on both sides using the top strap’s center line. Once fitted, secure the locking clips on both sides.

An animal’s neck diameter can change over time, so check collars periodically to ensure they remain comfortable and secure, especially if the animals are actively gaining or losing weight. A collar that is too loose or tight can lead to chafing around the neck.

Removing collars

Removing a collar is easier than attaching one. With the animal in the squeeze chute and the neck exposed, press up on the underside of a black plastic locking clip. A 10 mm Allen wrench fits the clip slot and makes removal easier. Unclip the black plastic buckle and remove the collar from the animal’s neck.

Proper fit is achieved when livestock can express their natural behavior without the collars interfering or falling off (Figure 3) (Audoin et al., 2025). Please note that cattle were safely restrained while collar fit was adjusted for demonstrative purposes only. Always be sure collars are properly adjusted for fit before releasing animals.

Halter™

Amber Dalke, University of Arizona

Halter was founded in New Zealand in 2016, and now has over 250,000 collars on beef and dairy cattle across New Zealand, Australia, and the United States as of 2024. The company specializes in collars for cattle. Their collars are not designed for small ruminants. This VF system requires multiple base stations and a 3–4-year contract. Collars are solar powered and estimated to last for 5 years. While the lifespan has not been rigorously tested in the US, the collars have been rigorously used and tested in New Zealand since 2016 and have a lifetime warranty. The collars are leased, so if the collar or battery breaks down, they send you a replacement free of charge. A subscription must be purchased. Halter is the only company that offers left and right stimulation, which should influence livestock to move directly in one direction to return to the grazing area. Each collared animal is trained to understand the cues, and Halter personalizes cues to each individual animal, which provides the positive stimulation on the left and the right to guide cows. Halter also has a vibration mode created to entice livestock to move forward. The Halter system became available in the U.S. during summer of 2024. In the current dairy platform, Halter offers data analysis packages that include reproductive tracking (heat detection, cycling rates, days to return to estrus, benchmarking mating performance, and others), grazing management tracking (rotation planner, fertilizer application records, benchmarking pasture performance, forage growth rate estimates, and others), and herd monitoring (individual cow behavior trends, health alerts, rumination, and herd grazing behavior trends).

Attachment mechanism

| Attachment | Attachment considerations | Tested | Effectiveness (5-Point Likert Scale) |

|---|---|---|---|

2 point attachment Image

Travis Mulliniks, Oregon State University |

| Tested at OSU and UA (2025 to present)* | Very effective |

Collar assembly

Halter collars arrive fully charged. If the charge has dropped, which is visible in the app, then placing the collar outside in the sun will allow it to charge. The app will allow you to track charge. Collars activate automatically when in contact with sunlight. If a collar does not activate automatically, the provided magnet will activate after touching the top of the collar. When the collar flashes blue, the collar has been successfully turned on or reset. Once the collar is connected to the network, the LED light will start flashing green. The collar is ready to be used. On average, one person can activate 100 collars in less than 30 minutes.

Tools needed

Tools needed include a magnet (provided with collars) to activate the collars. No other tools are needed since no assembly is needed (Table 3).

Recommendations for proper collar fit

As with any collaring system, spending time to get the right and proper fit is key. When the cow’s head is in a neutral position, the counterweight at the bottom of the collar should be slightly compressing the skin under the neck, and you should be able to fit three fingers between the collar strap and the neck of the cow (Figure 4). Both sides of the strap can be adjusted to get the correct and balanced fit. Ensure there is no more than a two-hole difference on each side of the strap, any more than that will cause the counterweight to not sit evenly on the cow’s neck. To test the fit, pull the collar on top of the cattle’s poll. If it goes over, the collar is too loose (Figure 5). Please note that cattle were safely restrained while collar fit was adjusted for demonstration purposes only. Always be sure collars are properly adjusted for fit before releasing animals (Audoin et al., 2025).

Nofence™

Amber Dalke, University of Arizona

Nofence is a Norwegian based company founded in 2011. The Norwegian Food Safety Authority allowed the use of their VF collars on goats in late 2017. Nofence is the only vendor with collars designed for cattle, sheep, and goats. Nofence relies on a cellular network system (2G & 4G) and requires that the collars be purchased. A subscription must also be purchased. When purchasing collars for the first time, a 12-month subscription must also be purchased for each collar. After the first 12 months, users can choose between a yearly subscription and a monthly subscription. Collars have a removable lithium-ion battery, as well as solar panels for recharging the battery while deployed. Collars are estimated to last between 5 and 10 years; however, this lifespan has not been rigorously tested in the US. Collars purchased from 2024 onwards have a 5-year warranty. The Nofence system became commercially available in the US during spring of 2024.

Attachment mechanism

| Attachment | Attachment considerations | Tested | Effectiveness (5-Point Likert Scale) |

|---|---|---|---|

Cattle collar silicone straps Image

Lara Macon, USDA-ARS Jornada Experimental Range |

| Tested at NMSU and JER* | Effective |

Sheep or goat collar silicone strap Image

Flavie Audoin, University of Arizona |

| UA and UCCE trials** | Effective |

* New Mexico State University (NMSU) & Jornada Experimental Range (JER)

** University of Arizona (UA) and University of California Cooperative Extension (UCCE)

Collar assembly

First, make sure all the batteries are fully charged. Batteries are not fully charged when shipped and it can take 11-12 hours (h) for a cattle battery and up to 7 hours for a sheep/goat battery to charge completely. Nofence includes chargers for their collars that plug into a wall outlet (Figure 6). Depending on the number of chargers vs batteries to charge, this step could require several days/ weeks.

Next, insert the batteries into the collars a day before deploying them. This allows time for the collars to install any firmware updates. As long as the collars have power and are in cell service, they should automatically update. The collars should make a start-up sound upon inserting the battery and the user will see the collars reporting in the mobile app. It is important to note, collars that have a battery inserted and are reporting for more than 3 days will be charged the subscription fee. Therefore, any collars that are not actively deployed or going to be deployed within 3 days should be stored with the battery removed.

If the user is redeploying collars that have previously been used, extra steps are needed to make the collars ready for deployment. First, make sure the batteries and battery slot of the collar are clean and free of debris. Next, check the hex screws that attach the top collar bracket to the collar unit. Make sure that no screws are missing or loose. Collar model C2.2 features two screws and collar model C2.5 features one screw. These screws ensure that the bracket and chains maintain contact with the metal pins of the collar unit. Loose or missing screws may interrupt this connection, resulting in potential collar malfunction (Figure 7). Avoid over tightening the screws, as this could damage both the collar and the bracket. Screws should be tightened to hand tightness.

Figure 6: Cattle, sheep & goat charger and battery. The LED indicator light will turn green when the battery is fully charged. Charging can take up to 12 h for the cattle batteries and up to 7 h for the sheep/goat batteries.

Photo credit: Lara Macon, USDA-ARS Jornada Experimental Range and Flavie Audoin, University of Arizona

Figure 7: Hex screw that has come loose on a Nofence C2.2 model virtual fence collar. A size 3 mm Allen key for tightening bracket screws is also recommended to have on hand.

Lara Macon, USDA-ARS Jornada Experimental Range

Tools needed

Nofence collars do not require assembly beyond inserting a charged battery (Table 4). The release buttons on the batteries can be difficult to depress by hand, so C clamp style vice grips (Figure 8) may help with battery removal when storing unused collars, but are not necessary. Adjusted to the proper width, vice grips can be used to help press the green button on either side of the battery to release it from the collar (Figure 8).

For sheep and goat collars, a battery removal tool is available and should be purchased to make the removal of the battery from the charger and collar easier (Figure 9).

Recommendations for proper collar fit

Collar fit is extremely important, both for animal welfare and safety and for proper collar function. Collars that are too loose can swing against the animal’s neck or chin when grazing, causing discomfort. Further, the animal may slip a foot through the collar or get the collar stuck on something if the fit is too loose. Conversely, a collar that is too tight may cause discomfort and could lead to chafing or irritation around the neck.

Proper collar fit ensures proper chain contact with the animal’s neck. A properly fitting collar should be able to sway slightly from side to side with the animal’s movement but should not be able to move drastically up and down the animal’s neck (Figure 10). For cattle, proper fit is when you can fit 3-4 fingers between the collar and the animal’s neck.

For small ruminants, if you are putting collars on a wool breed, it is recommended to put them on after shearing for better success in training the animals to the technology, especially the electric stimulus. For sheep, proper fit is when you can fit a finger under the squeezed neck strap (Figure 11). Please note that sheep were safely restrained while collar fit was adjusted for demonstrative purposes only. Always be sure collars are properly adjusted for fit before releasing animals (Audoin et al., 2025).

Figure 8: C style vice grips can aid in removing of batteries from many collars.

Lara Macon, USDA-ARS Jornada Experimental Range

Figure 9: Battery removal tool for sheep and goat virtual fence collars

Flavie Audoin, University of Arizona

Vence™

Amber Dalke, University of Arizona

Vence, an American based company, was established in 2017 and purchased by Merck Animal Health in 2022. Collars are designed for cattle, but the company is conducting research on small ruminants. The Vence system requires multiple base stations, each with coverage up to 9 miles. The collars use a single-use battery estimated to last 6 to 9 months depending on use. Additional batteries must be purchased. The collars are leased, so if the collar or battery breaks down, a replacement is sent free of charge. A subscription and batteries must be purchased. The Vence system became commercially available in the US in 2021

Attachment mechanism

| Attachment | Attachment considerations | Tested | Effectiveness (5-Point Likert Scale) |

|---|---|---|---|

Heavy-duty zip ties Image

Flavie Audoin, University of Arizona |

| Tested at the SRER* (2021-2022) | Not effective |

Shipping container tags Image

Flavie Audoin, University of Arizona |

| Tested at the SRER* (2022-2023) | Moderately effective |

Twist Lock Carabiner Image

Flavie Audoin, University of Arizona |

| Tested at the SRER, UCCE and SDSU**(2024 to present) | Moderately effective |

*Santa Rita Experimental Range (SRER, Arizona) using VenceTM CattleRider (ver. 2 rev. c-g, Vence Corporation, San Diego, CA). The changes in letters represent revisions of the collars with different designs.

** Santa Rita Experimental Range (SRER, Arizona), University of California Cooperative Extension (UCCE) and South Dakota State University (SDSU)

Collar assembly

Based on field trials at the SRER using Vence (ver. 2 rev. c-g), preparing collars for a collaring event requires time to open the battery cover, install the battery in the collar housing, close the battery cover, and label the collar housing (Figure 12). Anecdotally, one experienced person can prepare approximately 15 Vence collars in 30 minutes, which equates to ~3.5 hours to prepare 100 collars.

There are several strategies to reduce the time needed to prepare the collars depending on the size of the collaring workforce. For a smaller workforce (e.g., < 3 people) or for people new to collar assembly, it may be best to prepare all collars prior to a collar deployment. However, if more collars are prepared than used, batteries must be removed from the collar as the collar may not turn off if the battery remains installed. With a larger collaring workforce (e.g., >3 people) or when people have more experience, ~30 collars can be prepared before the collaring event and the remaining collars can be prepared during collaring. This requires at least one person dedicated to preparing collars as other team members collar animals and record data. In either scenario, an assembly line likely reduces the amount of time needed to prepare collars. During collaring, a preparation station containing collar components may be the most flexible way to prepare collars. This strategy is especially useful when the exact number of animals being collared is not known (Audoin et al. 2025).

Tools needed

In addition to the appropriate attachment mechanism, tools might include a cordless impact driver, cordless drill, socket and ratchet, impact socket, Phillips screwdriver, flat-bladed screwdriver, and spare batteries for drills and driver (Table 5). Additional equipment may be recommended by the VF vendor.

Recommendations for proper collar fit

For the success in the use of VF technology, proper collar fit is very important (Antaya et al., 2024b; Audoin et al., 2025). Vence recommends to test the collar fit by pulling the collar over the top of the animal’s head until the collar struggles to go over one ear. If the collar can be pulled over both ears, the collar is too loose (Figure 13). Please note that cattle were safely restrained while collar fit was adjusted for demonstrative purposes only. Always be sure collars are properly adjusted for fit before releasing animals (Audoin et al., 2025).

Summary

Virtual fencing (VF) systems are emerging technologies that allow livestock managers to control animal movement without physical fences. These systems generally include three key components: a digital interface to set virtual boundaries, GPS-enabled collars that provide auditory and electrical cues to guide animal behavior, and communication infrastructure provided by cellular towers with base stations used as intermediaries in some VF systems (Antaya et al., 2024). As of December 2025, four companies offer VF systems commercially in the United States: eShepherd by Gallagher, Halter, Nofence, and Vence by Merck Animal Health. Each company has developed distinct technologies and components that are not interchangeable between systems. While all systems share a similar purpose, collar designs, functionalities, and infrastructure requirements vary.

eShepherd

eShepherd, developed by Gallagher, is a New Zealandbased product that focuses on cattle. It is unique in offering connectivity via both cellular networks and base stations, with a range of 2 to 4 miles depending on environmental conditions. The solar-powered collars have an estimated lifespan of 7 to 10 years, although their durability has not yet been tested on U.S. rangelands. The collars require activation with a magnet and can be monitored through a web app. Proper collar fit is ensured when there is a fistwidth gap between the collar and the animal’s neck. The collars have a 750-pound breaking strength. Collars can be attached and removed without additional tools, and bulk data upload features are supported through the eShepherd app.

Halter

Halter, also based in New Zealand, specializes in cattle collars and began US operations in the summer of 2024. The system requires multiple base stations and a multiyear service contract. Halter's solar-powered collars last approximately five years and come with a lifetime warranty. This system stands out for offering left and right directional stimulation, as well as vibration cues to move animals forward. The technology is tailored to each animal. Collars arrive fully charged, are easy to activate with a magnet, and do not require assembly. Fit is critical and achieved when the counterweight compresses the skin slightly and three fingers fit between the strap and neck.

Nofence

Nofence, a Norwegian company, is the only VF vendor to offer collars for cattle, goats, and sheep. This system relies solely on cellular connectivity and uses solarpowered collars with an estimated lifespan of 5 to 10 years. Nofence collars require battery charging, which can take 11–12 hours per cattle unit and up to 7 hours per sheep/ goat unit. Before deployment, users must ensure batteries are charged, collar brackets are secure, and firmware is up to date. Tools like vice grips and Allen keys may assist with battery removal and bracket adjustments. Proper collar fit is essential for both animal safety and effective functioning. Collars should not hang loosely or swing significantly

during animal movement.

Vence

Vence, an American company acquired by Merck Animal Health in 2022, has been commercially available in the US since 2021. Designed for cattle, the Vence system uses leased collars powered by single-use batteries estimated to last 6 to 9 months depending on use. It requires multiple base stations, each with a coverage range of up to 9 miles. Collars involve more complex assembly, including battery installation and labeling, and are best prepared in advance or via an assembly line during collaring events. Field trials have tested various attachment methods. Proper fit is confirmed when the collar resists being pulled over the animal’s ears but still allows natural movement.

As the technology continues to evolve, additional virtual fencing companies may enter the US market in the future, offering more options and innovations for livestock producers.

Disclaimer

There are several companies that manufacture hardware and software including eShepherd™ from Gallagher™, Halter™, Nofence™, and Vence™ from Merck Animal Health. Virtual fencing components from different manufacturers are generally not interoperable or interchangeable. Specific components, GIS data needs, software protocol, software training, frequency and duration of the cues, GPS error, livestock collaring, and livestock training protocols may vary depending on the manufacturer. Follow the manufacturer’s recommendations and guidelines. The University of Arizona does not endorse a specific product. The use of trade, firm, or corporation names in these methods is for the information and convenience of the reader. Such use does not constitute an official endorsement or approval by the USDA Agricultural Research Service, of any product or service to the exclusion of others that may be suitable.

Any feedback with your personal experience or reactions to the virtual fence technology would be appreciated and might be helpful in revising this document for future users.

Acknowledgements

This material is based upon work that is supported by the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, U.S. Department of Agriculture, under award number 2021- 38640-34695 through the Western Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education program under project number WPDP22-016. USDA is an equal opportunity employer and service provider. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the view of the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

This work is supported by the AFRI Foundational and Applied Science Program: Inter-Disciplinary Engagement in Animal Systems (IDEAS) [Award no. 2023-68014-39715] from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture.

Additional funding for the University of Arizona’s Virtual Fence program was provided by Arizona Experiment Station, the Marley Endowment for Sustainable Rangeland Stewardship, Arizona Cooperative Extension, and The Nature Conservancy.

For additional information about virtual fence, visit Rangelands Gateway.

References

Antaya, A.M., Dalke, A., Mayer, B., Noelle, S., Beard, J., Blum, B., Ruyle, G., Lien, A., 2024. What is virtual fence? Basics of a virtual fencing system (No. az2079). University of Arizona Extension Publication az2079, Tucson, Arizona, USA.

Antaya, A., May, T., Burnidge, W., Mayer, B., Audoin, F., Noelle, S., Blum, B., Blouin, C., Lien, A., Dalke, A., 2024. Foundations of Virtual Fencing: Strategies for Collar Management (No. az2095). University of Arizona Extension Publication az2095, Tucson, Arizona, USA.

Audoin, F., Antaya, A., May, T., Burnidge, W., Mayer, B., Noelle, S., Blum, B., Blouin, C., Lien, A., Dalke, A., 2025. Foundations of Virtual Fencing: Collar Deployment Basics (No. az2124). University of Arizona Extension Publication az2124, Tucson, Arizona, USA.

Ehlert, K.A., Brennan, J., Beard, J., Reuter, R., Menendez, H., Vandermark, L., Stephenson, M., Hoag, D., Meiman, P., O’Connor, R.C., Noelle, S., 2024. What’s in a name? Standardizing terminology for the enhancement of research, extension, and industry applications of virtual fence use on grazing livestock. Rangel. Ecol. Manag. 94, 199–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rama.2024.03.004